July 15, 2025

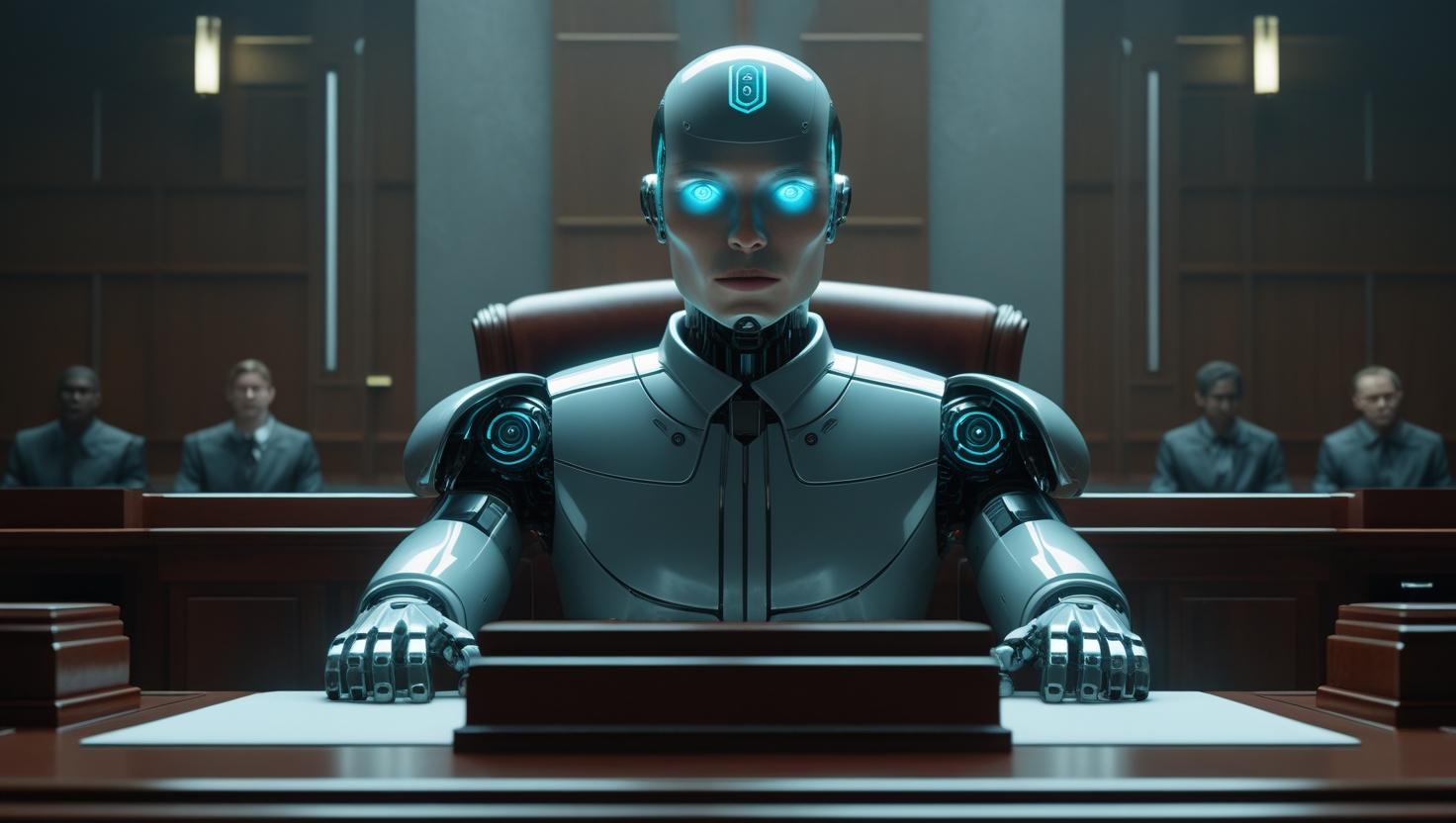

Justice by Numbers: How AI Is Sentencing People

When the Law Is Written in Code

Picture this: you’ve just been found guilty. Before the judge declares your sentence, they consult a screen.

An algorithm calculates your “risk score”—your likelihood to reoffend, your potential for rehabilitation, and the level of threat you supposedly pose.

Then the number flashes: 72.

That number might add months—or years—to your sentence.

Welcome to the world of predictive justice, where algorithms are playing judge, jury, and sometimes even parole board.

What Is Predictive Justice?

Predictive justice refers to the use of artificial intelligence and machine learning to:

- Forecast recidivism (the likelihood someone will reoffend)

- Assess risk scores to influence sentencing severity

- Guide parole decisions based on behavioral predictions

- Recommend pretrial detention based on probability of fleeing or danger

At its core, predictive justice turns people into data points, and crime into a statistical equation.

The Appeal: Efficiency, Objectivity, Scale

Supporters of AI in the justice system argue that it can:

- Reduce human bias in sentencing

- Increase consistency in legal decisions

- Help manage overloaded courts and prisons

- Provide data-driven insight into criminal behavior

- Allocate resources more efficiently

It’s presented as “smart justice”—using tech to remove emotional, arbitrary, or prejudicial judgments from legal outcomes.

But in reality, the math can be just as flawed as the humans it replaces.

How These Systems Work

Most sentencing or risk assessment algorithms are built using machine learning models trained on historical crime and incarceration data.

They take inputs like:

- Age

- Number of prior offenses

- Type of crime

- Neighborhood or ZIP code

- Education or employment history

- Criminal records of family members

- Past court appearances

They then output a risk score—a number that represents the likelihood of reoffending, failing to appear, or engaging in future criminal behavior.

Judges are advised to consider this score during sentencing, but in practice, it often becomes decisive.

Garbage In, Injustice Out

Here’s the catch: these systems are only as good as their training data.

And criminal justice data is deeply flawed.

- It reflects decades of over-policing in certain communities

- Arrest records often don’t indicate guilt—just who got caught

- Recidivism data can be skewed by surveillance bias

- Socioeconomic and systemic factors get encoded as “risk”

As a result, AI models often reproduce and amplify existing inequalities—not eliminate them.

A Case Study in Bias

In a notable audit of one prominent risk-scoring tool, it was found that:

- People flagged as “high risk” often didn’t reoffend

- People marked “low risk” sometimes committed serious crimes

- Certain demographic groups were twice as likely to be misclassified as high risk—even with similar histories

This isn’t accidental. It’s structural bias, coded into logic.

Opaque Logic, Real-World Consequences

Many of these systems are proprietary. That means:

- The code is secret

- The variables are unclear

- There’s no way to challenge how scores are calculated

Imagine losing years of your life to an algorithm you can’t inspect, question, or appeal.

This violates one of the core tenets of justice: the right to understand and challenge evidence against you.

The Illusion of Objectivity

AI feels neutral because it’s mathematical.

But when models are trained on historical injustices, they don’t eliminate bias—they weaponize it at scale.

Risk scores become a form of digital profiling, where assumptions are baked into every recommendation:

- Where you live becomes a proxy for threat

- Past police encounters become predictors of your future

- Your family background becomes a liability, not context

This isn’t objectivity. It’s automated discrimination.

When Prediction Becomes Punishment

The use of AI in sentencing fundamentally shifts the legal system from punishment for what you did to punishment for what you might do.

This is preemptive justice—punishment based on probabilities, not actions.

It introduces a dangerous philosophy:

"You’re not being punished for who you are—but for what you might become."

This undermines presumption of innocence and the belief in rehabilitation.

The Rise of Algorithmic Parole Boards

Beyond sentencing, AI is now being used in parole decisions.

Algorithms decide:

- Who’s eligible for early release

- Who should remain behind bars

- Who poses too much “risk” to the public

But these decisions are made with limited context, and often without public accountability.

Even worse, they can override the judgment of parole officers or correctional staff—substituting human empathy for statistical logic.

Automation Creep in Legal Systems

We’re seeing a trend where more and more legal decisions are being outsourced to machines, including:

- Bail setting

- Plea deal recommendations

- Jury selection modeling

- Sentencing ranges

- Probation risk scoring

Each of these applications claims to improve efficiency.

But efficiency is not the same as justice.

What a Just AI System Would Actually Require

If AI is to play any role in the courtroom, it must meet strict criteria:

✅ Full Transparency

No black-box models. Every logic chain should be reviewable by defense teams and legal experts.

✅ Bias Auditing

All algorithms should undergo regular, independent audits for racial, gender, economic, and neurodiversity bias.

✅ Explainability

AI must provide plain-language explanations for its decisions—understandable by humans, especially the accused.

✅ Contestability

Defendants must have the legal right to challenge risk scores and the inputs used to calculate them.

✅ Human Oversight

AI should assist—not decide. Judges must retain ultimate authority, and be trained to interpret AI outputs critically.

Can the Law Be Fair When It’s Written in Code?

Law has always been imperfect—but it was human. Flawed, but flexible. Biased, but contextual.

Algorithms lack that flexibility.

They don’t understand trauma, systemic injustice, or the possibility of transformation. They don’t see remorse or change. They see risk vectors.

If we give them too much power, we risk building a legal system that’s mechanical, not moral.

Final Thought: Numbers Don't Understand Justice

Justice is not a math problem.

It can’t be solved by probability.

It requires context, compassion, contradiction.

AI can help surface patterns.

It can help flag inconsistencies.

But it cannot replace judgment.

Because justice isn’t about what’s likely.

It’s about what’s right.

💬 What’s Your Verdict?

Should algorithms have a say in court decisions?

Have you or someone you know been impacted by automated justice?

Join the conversation on Wyrloop — and help us advocate for transparency, fairness, and a more human digital justice system.